Not every dog and cat lives in the comfort of a home filled with toys, treats and food bowls. In fact, 50,000-100,000 don’t have a home at all … and neither do their owners. But thanks to Dr. Jon Geller and other veterinarians like him, these pets and their owners have access to preventive medicine and more in pop-up clinics around the country.

“Veterinary medicine isn’t about working nine to five and then going home,” said Dr. Geller, an emergency practitioner in Fort Collins, Colo. “In addition to providing care for those who cannot afford it, we need to address both the mental and physical health of pets and their owners, since they are so interconnected, both physically and mentally. It really is a One Health issue, where the health of the pet and owner are intertwined.”

“Veterinary medicine isn’t about working nine to five and then going home,” said Dr. Geller, an emergency practitioner in Fort Collins, Colo. “In addition to providing care for those who cannot afford it, we need to address both the mental and physical health of pets and their owners, since they are so interconnected, both physically and mentally. It really is a One Health issue, where the health of the pet and owner are intertwined.”Veterinarians are taking this need very seriously and mobilizing to bring care to those who cannot afford it, thereby reaching pets that are living in tents, cars and cardboard boxes. Dr. Geller will be presenting “Street Medicine,” a little-known, benevolent side of the profession, at the American Veterinary Medical Association Annual Convention, July 21-25, in Indianapolis.

“There is a very strong bond between the homeless and their pets, which are often viewed as their only friends,” said Dr. Geller. “The bond is such that homeless people may think they cannot live without their pets and become suicidal.”

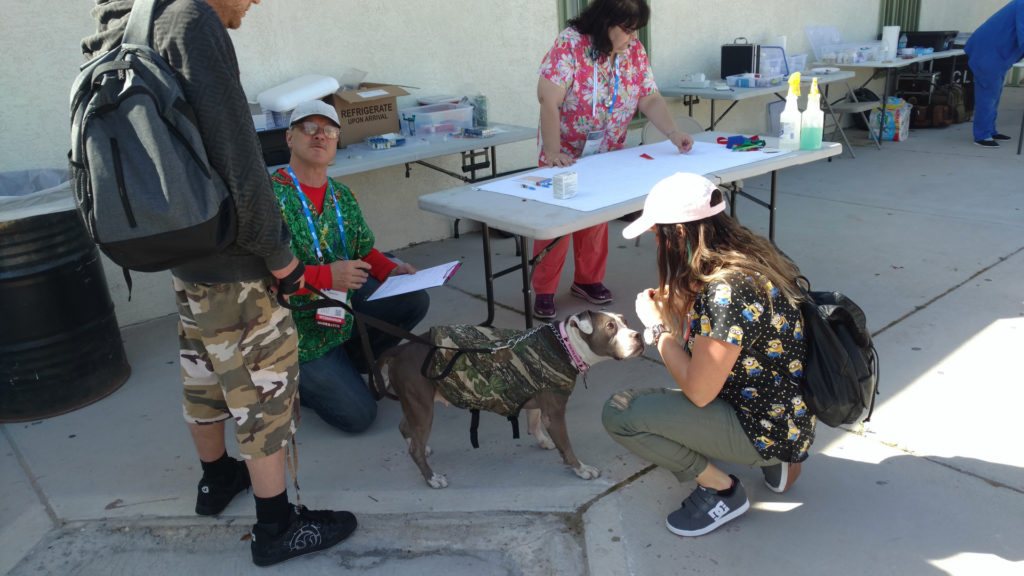

Enter Dr. Geller and a team of volunteer veterinarians and technicians—appropriately named the Street Dog Coalition. They scout locations, typically near shelters, and set up monthly, doggy-focused MASH units in cities throughout Colorado. Other teams are doing the same in Florida, Massachusetts, Nevada and Kansas.

Clients are often not plugged into social media, so advertising is done by word of mouth by homeless advocates as well as flyers in shelters and free meal events. Common treatments included basic exams, vaccinations and addressing common medical problems like allergies and arthritis.

“We are being creative and frugal,” said Dr. Geller. “We’re not doing anything fancy, but we are ensuring the standards of care are being met.”

Diagnostics are completed with portable blood tests and urine dipsticks and even an ECG can be run, using an iPhone. For spays and neuters and other surgeries, Dr. Geller refers clients to local veterinarians who donate or reduce the cost of in-office procedures. His own non-profit organization, The Ladybug Fund, often makes up the cost difference, as do the Velvet Assistant Fund, the AVMA Foundation, and FACE Foundation in San Diego, just to name a few. The homeless never pay a penny for any pet treatment or medicine, which are donated or obtained at minimal cost.

When his free clinics are held in a big city, Dr. Geller’s team sees between 50 to 100 pets each day. Smaller cities attract half that number. He says, as more veterinarians become involved, the number of homeless-owned pets is a very manageable number to treat.

“There is a stigma about being homeless, and some may hold the opinion that homeless shouldn’t have pets, that it’s financially irresponsible,” said Dr. Geller. “As I treat these pets, I’ve been surprised and realized that, in some ways, they have a better life than do our housed pets.”

For instance, he cites that these pets spend most of their time outdoors and have constant companionship. They are also socialized, active and rarely overweight—and they are not often hungry because their owners will feed them before they themselves will eat.

Conversely, homeless pets run twice the risk of contracting mosquito- and tick-borne diseases. Rabies is also more common in pets living outdoors. But when an owner has no home, empty pockets and little food, a visit to a veterinarian is not going to happen without help. In addition, the homeless are sometimes wary of going to these free clinics, fearing that authorities will impound their pets, ticket them for no pet license, or even charge them with immigration issues.

The homeless living with pets also can be at risk. Dr. Geller worked with a homeless man who lived in a van with an egg-laying chicken and two cats. The man was covered in reddened plaques on his skin that were most likely from a parasite living on either the chicken, the cats, or both. He couldn’t afford new bedding.

The need to treat the homeless and their pets is great, and Dr. Geller is always on the lookout for more help, His recruiting efforts have led to many veterinarians joining the cause.

“The future looks bright,” he said. “Vet students are leading the way, like the University of Wisconsin students who began WisCares, a medical service organization for pets of the homeless. The next generation of veterinarians is very passionate about making a difference.”

And that difference is definitely doable. Dr. Geller has worked the numbers: 50,000 veterinarians donating two to four hours a month organizing upcoming clinics. “We can go upstream, expand beyond the homeless, and treat low-income pets that are not getting street care. We can do something about the affordability gap and exceed our obligations as veterinarians.”

2 Comments

Programs like this are so important to the community!

Are there any vets in the Lexington/Louisville are doing this?