Reposted in honor of Ranny Green (1939-2024)

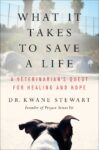

“What It Takes to Save a Life: A Veterinarian’s Quest for Healing and Hope,” by Dr. Kwane Stewart. HarperOne, $28.99.

This powerful and engaging narrative takes you to the streets, animal shelters, and veterinary hospitals while capturing colorfully fluid and life-altering profiles along the way. Stewart, a San Diego-based practitioner, has been treating the beloved pets of street people for a decade and, in the process, saw his efforts save his own life, too.

“I was isolating myself and cutting people off in my life,” he acknowledges.” My Mom would call, for example, and I wouldn’t return her call for days. I was slowly pulling away, and this brought me back.”

Yes, there are plenty of feel-good stories involving pets of the homeless, conversely, there are the gut-wrenching days of euthanasia both in the shelter and owners’ homes. It’s no secret that veterinary medicine suffers from one of the highest rates of professional suicide, which is reflected here with substance and grit.

What gives this book coherence is the spirit of challenge and dissent along with the heart and soul of pet ownership. Throughout there is an umbilical connection between the patients and owners, sometimes brimming with goofy humor and paragraphs later a sense of anxiety atop a brittle landscape.

Stewart writes candidly, “Even in their darkest moments, the homeless people I met had their loyal companions by their sides. Homeless people are loving, dedicated pet owners – which I hadn’t thought the case before I started my work. . . . To a pet, their owner is their universe. But we go to work and leave our pets alone sometimes eight, ten, and twelve hours a day, and they just sit and pine for us. Homeless pets, in contrast, get plenty of exercise and fresh air.”

Each animal owned by a homeless individual, he emphasizes, provided him with a deeper understanding of the human-animal bond. “I saw homeless people feed their pet before they fed themselves. I saw them give their last dollar to care for their pet. They sustained each other. I can’t tell you how many times people told me their animals were their reason for getting up in the morning.”

Dr. Kwane Stewart with a canine friend

With vigorous storytelling, the author takes the reader through a pathway of undergrad and graduate schooling where he learned many valuable life lessons in addition to fine-tuning his surgery and diagnostic skills. That’s also where he discovered that he wanted to practice on companion animals instead of large counterparts like cows and horses.

Coping with death in veterinary school at Colorado State University was challenging, Stewart concedes. “You’re tasked with a giant responsibility as a vet., but you’re not here by mistake. You’ve earned your spot and you’re going to get through it. You have the coping skills – you’ve trained for this, and you’re going to be OK. Just don’t worry too much.”

“ . . . It takes calibration to love and to give, and, ultimately to lose – as most pet lovers survive their pets. Too much heart and the veterinarian, vet tech, pet lover, or advocate will burn out. Too little heart and they wouldn’t be there in there in the first place, or they wouldn’t be trusted to do right by the animals in their care. But calibration is not easy. And the hard truth is that not everyone can do it and some have to walk away to preserve their mental health. There’s no shame in that.”

“I think what makes me capable of guiding people through the end of their pet’s life is that I don’t fear it. It’s a natural part of life’s cycle, and the constant reminders of it make me less anxious, not more.”

Veterinary mental health receives plenty of attention here with Stewart citing the difference between burnout and compassion fatigue. “Burnout isn’t exactly easy to address, but at least it’s more tactical. It involves changing systems or changing expectations of just how much work can actually be done by one person. Compassion fatigue is much harder to recognize and support. Everyone has to find their own way through compassion fatigue because there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. And it’s not something that goes away as much as it’s something to be managed.”

Whether they’re on the streets, in an assisted-living facility, or at home, dogs, Stewart emphasizes, are life preservers for the soul, whether it be for an owner or veterinarian, who both experience loneliness, boredom, or a need for an exercise partner.

Stewart’s emotionally rich memoir is one of sharp contrasts, too. From caring for the pets of the homeless and that attending undercurrent of emotion, he later serves as the safety overseer on a Hollywood movie set. That job begins well before filming when he receives the script and flags the scenes involving animal actors. Here he writes a risk assessment for that scene and the movie as a whole.

In that role, he works with animal trainers as well as directors and producers. “The trainers love it when I’m on set,” Stewart establishes, “because while they of course know better than anyone when their animals are getting tired, they would rather someone else have the role of telling the director. After all, they want to be hired by that director again.”

The Venerable Ranny Green: A Nose for News And A Grand Guy Too!

Originally posted May 28, 2023