When it comes to loaded therapeutic toolboxes, pets top the list. From birds to pigs and horses to dogs, their ability to assist mankind is legend. Often the need is no greater than that of our proud veterans suffering from a wide gamut of wounds – some visible, others not.

The Maine assemblage is the outgrowth of Guerin’s working relationship with the former First Lady from her White House days and the co-author’s friendship with Jean Becker, the president’s chief of staff. The Becker-Guerin friendship was instrumental in Mrs. Bush, a dog lover, writing the foreword for this volume and the authors, veterans and their animals attending the Maine book launch party.

Vets and Pets veers from frustration and challenge to a dollop of delight, one vignette after another. Each subject faces a catalog of challenges but his/her eventual rescuer(s) that supplies the needed emotional heft is an animal or bird.

The numbers are staggering, the authors note. The U.S. Department of Defense estimates that more than 300,000 veterans have been injured in Iraq and Afghanistan, from physical wounds to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic Brain Injury.

Each chapter of Vets and Pets is a lively and flavorful narrative of the epitome of the service-pet movement with a powerful mosaic-like feel boasting more substance than splash.

Here’s a taste of what’s inside:

U.S. Army Specialist Tyler Jeffries lost his legs and suffered severe burns stemming from an IED explosion in Afghanistan in 2012 and was left reeling physically and psychologically upon returning to the U.S.

But that was about the change when he “fell in love” with European Dobermans while attending a benefit in North Carolina. Enter a private donor from New York who paid the cost of the dog and subsequent training (an estimated $55,000) for Apollo, who was to become Jeffries’ “lifeline” moving forward.

“In the four years that Tyler and Apollo have been a team, Tyler has been transformed,” the authors say. “No longer is he afraid to be seen in public, fearing ridicule and piercing stares from people.

“. . . The one quality about these giant dogs that people don’t often get to see while they are working is their very human like and intuitive side.”

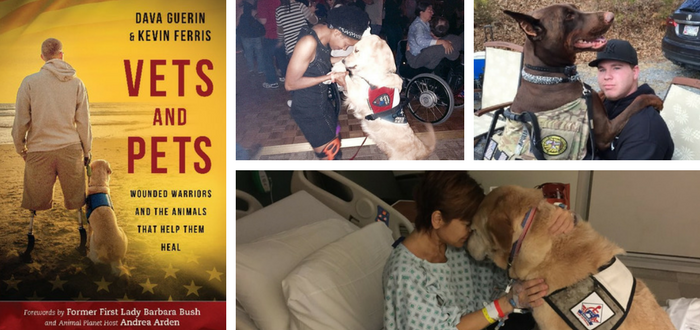

Apollo, a European Doberman Pinscher, can’t get enough of Tyler Jeffries. Apollo has been Jeffries’ “lifeline to recovery” from multiple injuries sustained from an improvised explosive device explosion in Afghanistan. Photo by Dava Guerin.

Dealing with PTSD and reaching out for help hasn’t been easy for Texan Jimmy Didear, a Marine combat vet who served in Vietnam and dealt with the nightmare PTSD for decades. One of the biggest lessons he took from the Marines was, “You don’t quit, even if you have a hole in your shoulder or your leg. Don’t quit. Just keep going.”

The Didear who returned home from Vietnam wasn’t the same one who left. This one was miserable, couldn’t sleep and considered suicide multiple times, after living in fear of land mines throughout much of his deployment.

Three decades later he acknowledged needing help and joined a local group, his medications were adjusted, but most important he met an Iraq veteran with a service dog. He asked his counselor about service dogs and was encouraged to apply for one. And voila! He connected with a San Antonio organization, Train a Dog Save a Warrior, which brings together rescue dogs and veterans suffering from PTSD and is dedicated to creating a “positive, nonjudgmental, unconditional relationship desperately needed by both.”

Working with a local trainer in 2015, seven dogs were rejected before Didear found Max, a Chocolate Labrador/American Bull Terrier. Through extensive training, the two established a strong friendship and mutual respect. “He depends on me, and I depend on him. That’s why we’re a team. He and I are closer than even my family because he’s with me all the time,” says Didear.

“These dogs will accept you for who you are and what you are regardless of what you’ve done, and they don’t judge you. All we want is to be accepted. We’d like to come home, but some of us are stuck in time. We have to learn to live with that for the rest of our lives. There’s no fix.”

There’s no limitation to the joy a service dog can provide a once-beleaguered veteran – or anyone, for that matter. Here, Timber a Golden Retriever, enjoys a dance with Shanda Taylor at a veterans’ event. Photo courtesy Shanda Taylor.

There has probably been no other veteran in the country who has been more of an ambassador for service dogs for vets than Shanda Taylor. Always mission oriented, the 23-year Army veteran – first a Military Policewoman and later a nurse – the mother of three was injured May 2004 in an auto accident while en route home to Redmond, Wash., (a Seattle suburb). She declined to be admitted to the hospital but what followed in the weeks, months and years later left her a changed woman and with an eventual diagnosis of Traumatic Brain Injury, plus fibromyalgia, which is characterized by chronic pain, sleep and memory issues.

“I went overnight, like in an instant, to not being able to wash the dishes or being able to read,” she recalls. “I knew the words, but I couldn’t put them together long enough to read a sentence.” Two years after the accident she was medically retired from the Army.

Enter Ranger, a Golden Retriever that segued her from the doldrums of despair to a more confident, calm presence while raising the three girls amidst a divorce. In addition to his at-home duties, Ranger helped lead the affable Shanda into a nationwide veterans social world of conventions and seminars where she has become a poster advocate for service dogs for veterans.

She’s been there, done that. “It’s the PTSD and TBI sufferers who get overlooked in this country,” she emphasizes. “You pass them on the street or in a hallway and everything looks normal. But many of them are hurting enormously inside. A dog or another pet can turn their lives around.”

Ranger died in 2015 of cancer, and Shanda’s new Velcro partner is Timber, another Golden. One of Shanda’s daughter, Danielle, captures Ranger’s influence beautifully while visiting with her Mom: “Mommy, Ranger was not a dog. He was something beyond that.”

Yes, but these are all dogs, you say. Other featured subjects found emotional support and a new-found reason to live from birds, pigs, cats and horses.

Patrick Bradley shows a veteran how to hold Sarge on a glove. Photo courtesy Avian Veteran Alliance and Patrick Bradley.

For Patrick Bradley, an Infantryman in Vietnam who suffered shrapnel injuries body-wide from a Vietcong mortar, it was the wounds people didn’t see that left a lasting impact. Through a tip from a Walter Reed Army hospital doctor, he found birds (bald eagles) that enabled him to exorcise his demons and move on a pathway leading to a variety of professional endeavors impacting not only himself but other veterans, too.

“These birds are deep and fierce and they don’t often reveal their feelings like dogs. But when they sit on a wounded veteran’s arm and spend time with him, they learn to trust again. So does the warrior. I always tell people when they ask me the difference between a dog, a horse or a raptor and how they affect veterans with PTSD that, with a dog, it knows when you are feeling down. It’s a tactile experience for both the animal and the human, the dog soothes you and you soothe the dog. Birds of prey also know when you are stressed and show that by trying to fly away, fidgeting on the glove or appearing nervous. The birds react that way to a veteran’s stress level, but they can’t be calmed down just by someone petting them. So if veterans who have issues and flashbacks see the bird reacting to their stress, they have to consciously work on themselves to calm the bird down. It ultimately motivates veterans to look inside themselves to solve their problems.”

In the case of Col. John Mayer, commander of the U.S. Marine Corps Wounded Warrior Regiment at Quantico, Va., it was a matter of metaphorically getting a leg up for those involved in the program, helping strengthen in mind, body and spirit. He eventually partnered the Wounded Warrior Regiment’s riding program with the Semper Fi Fund, founding the Jinx McCain Horsemanship Program.

Mayer has put his own brand on the approach. “I’m just a guy who loves horses and being a cowboy. What I say is, ‘We’re gonna go out and go cowboying.’ We get them out there where they do a hard day’s work and accomplish something. There are great benefits in that for your spirit. You’re breathing fresh air, and we try to go places that cell phones don’t work so they are not tied to any of their troubles at home. We sleep around a campfire, we cook around the fire. We never stay in hotels. We stay where you have to rough it – the tougher, the better.”

Issac, a Golden Labrador Retriever mix, comforts Leslie Nicole Smith while she was hospitalized at Walter Reed National Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. Issac was saved at the last minute from euthanasia in an animal shelter and has served as Smith’s Velcro partner for many years after she underwent a leg amputation. Photo courtesy Leslie Nicole Smith.

He argues that focusing on cowboy activities helps restore veterans’ confidence and “reminds them of the abilities they already have.”

Participants are 70 percent or greater disabled or who can’t find a meaningful job or won’t because of PTSD or Traumatic Brain Injury. In late 2016 there were 31 apprentices, most of whom were Jinx McCain alums.

Mandi Tidwell found the soothing presence of pigs – yes, that’s right! – the panacea to recovery following a dislocated hip in U.S. Army basic training, resulting in an honorable discharge. It eventually led her to founding Hooves Marching for Mercy, a sanctuary in Douglassville, Ga., where porcines and veterans find a “safe and nurturing place to reclaim their lives together.”

Why pigs? Why not! “The truly amazing thing about them is their intelligence, long-term memory and compassion. Believe it or not, pigs also suffer from PTSD. To me, that is the perfect combination – pigs and veterans helping each other,” says Tidwell. And she adds, they are sentient beings that have a conscience and can learn right from wrong.

After leaving the Army and a failed marriage, Tidwell, who was diagnosed with lupus in 2010, has found solace in the healing powers and emotional support served up by these porky characters, who bond for life with their humans and desire to be with them 24/7. “My pigs are the reason I get out of bed in the morning,” she emphasizes.

Vets and Pets is a kaleidoscope of this kind of storylines with emotional heft and stylized narratives across a broad landscape of psychological gymnastics. The pets featured throughout are the tonic that shaped the character and saved the lives of many onetime disillusioned veterans. And in the process, the reader is the beneficiary, too.