Reposted in Honor of Ranny Green (1939-2024)

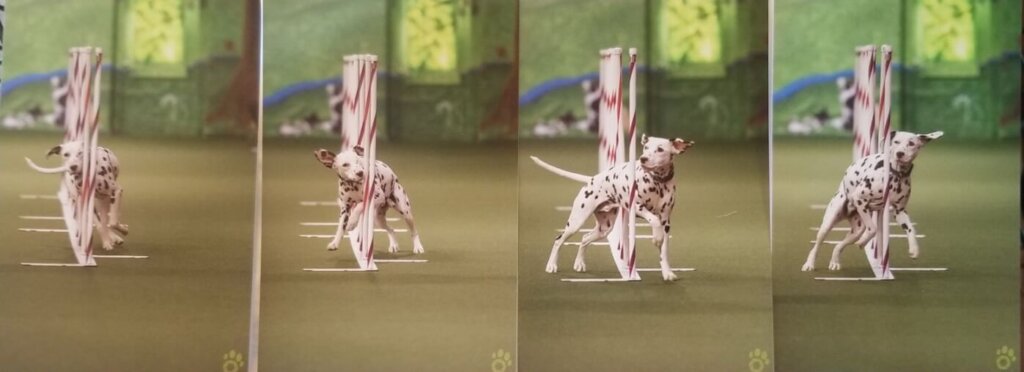

Home Page Photo Credit: Junior’s favorite agility skill is the weave poles. Photo courtesy Paws Imagery Mike O’Leary.

Here, the 4-year-old Dalmatian shows his physical acumen in the broad jump. Photo Courtesy Paws Imagery Michael O’Leary

Originally posted September 23, 2021.

Since March 18, 2017, Dawn Eliot-Johnson’s life has been all about focus and commitment. That’s when the Maine Dalmatian breeder greeted a litter of four – Junior, Bonsai, Rock and Juniper — via Caesarean section that was to eventually open new horizons and a salad mix of challenges. Eliot-Johnson has owned Dals for 29 years and bred them since 2005, never producing a deaf one — until that day.

The manager of an emergency veterinary hospital, she always maintained a close eye on the puppies. “Junior was the last to open his eyes,” she recalls. “He was much slower to mature. When the others would hear me enter the room, he continued sleeping and was the last to wake up. At three to four weeks, I became worried he was not hearing much, or at all.”

At four weeks, she began training all four to sit, using a clicker. Junior wasn’t hearing the clicker but he was reading his owner’s facial expressions and hand gestures. At that point, Eliot-Johnson began practicing sign language.

Then there was the lightbulb moment when his body language changed upon realizing he sat when Eliot-Johnson commanded. He followed with tail wagging and his ears moved back like a smile. He was a super proud puppy.

At 6 weeks of age the litter was taken to a veterinarian for BAER testing.

Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (BAER), also known as Brainstem Evoked Potential (BSEP), is an assessment that can be used to evaluate the hearing in dogs, cats and other domestic animals.

Not only does the test measure hearing, but it can also be used to test brainstem functionality. In relation to hearing, the brainstem transmits information to parts of the brain for interpretation. While most patients are awake for testing, some may require minor sedation for an evaluation.

During the procedure, the neurologist places two foam headphones into the patient’s ears and inserts needle electrodes under the skin on the head. Click sounds are transmitted through the headphones and the electrical response is recorded to assess hearing in both ears. The test will not check their ability to hear different levels of noises, as only a one sound at a single preset volume is used. The procedure is non-painful and presents no danger to the patients.

Results revealed Junior was totally deaf.

“I broke down and cried,” Eliot-Johnson recalls. “In fact, I cried for a week.”

Suddenly, she and her husband, Chris Johnson, were facing a push-and-pull of emotions on new turf. “My concerns had been if I place him with a family how do I know that he won’t be harmed because training a deaf dog is challenging. Or what if he gets away? Or would new owners abuse him because he doesn’t understand them? I couldn’t live with the thought of what might happen if he were put in the wrong hands. It would gnaw at me for a lifetime.”

Owner-handler Dawn Eliot-Johnson runs alongside Junior as he clears a hurdle.

Quickly, the couple decided Junior was a keeper, prompted somewhat by Eliot-Johnson’s exhaustive research focusing on living – and competing – with a deaf dog. In the mix she reached out to veterinarians, trainers, breeders, training manuals, rescue groups with experience with deaf dogs and the internet.

“Ultimately, it came down to Chris and I wanting what was best for Junior and not having to wonder what might happen to him months or years later,” she adds. “He was from my breeding and I stand behind them. Why would this be any different?”

In early puppyhood, Junior displayed a propensity to learn and try new things. “He was a star in his puppy agility class,” Eliot-Johnson says. At 6 months of age, Junior was fully comfortable with agility and was running full courses in practice. He was not eligible to compete in AKC agility trials, however, until 15 months of age.

Eliot-Johnson faced more hurdles from naysayers than she did from Junior running on course. “The more negative feedback I received the more it made me want to prove them wrong. There were many who said he shouldn’t be put through the rigors of competition because of his deafness. It left me feeling angry, hurt and sad.”

After each weekend trial, Mom makes Junior pose for a photo with his colorful array of ribbons.

Witness the 17 American Kennel Club titles, of which 13 are agility. In the process of training Junior, she has blossomed into a fighter for those with disabilities. She has studied American Sign Language, putting it to practice with Junior in both training and in agility competition throughout the Northeast.

“It’s been a work in progress,” she concedes. “I started with obedience signs, then segued to ASL.” COVID has left its own challenge. When required to wear a mask, Eliot-Johnson worries Junior cannot see her smiling at him, prompting her to teach him blinking or winks of her eyes to comfort him, which he learned quickly.”

Does she see agility as a 50/50 handler/deaf dog proposition when it comes to success? “It’s tilted a bit more on the handler,” she responds. “If the handler doesn’t Q the correct path, the dog doesn’t know where to go and might simply take what is in front of him.”

Training a deaf dog leaves little room for error with body movements. One little flick of a finger or missed step can put him on the wrong path. “So it’s almost always my fault if he does something wrong,” she concedes. “Just a few weeks ago I was running with him in a trial and my pants felt loose. So I pulled them up and with that small movement I pulled him off a jump. It was totally my fault.”

“The driven Dalmatian is always thinking outside the box,” says Eliot-Johnson. “He could be searching for the next thing to do, whether it be learning or showing off.”

Junior gives Mom a good-luck kiss before a run. Photo courtesy Jim Badger

The team’s steady progress has prompted the formation of an informal fan club. “It’s been gratifying,” Eliot-Johnson says, “and has led to many new friendships.” Make no mistake about it, the duo’s umbilical connection extends far beyond agility venues. The 51-pound Junior is in Camelot on the owners’ 15-acre hobby farm in Bryant Pond, Maine, population approximately 1,300. The farm is also home to their four other Dalmatians, a quarter horse named Buddy and a Mustang, Liberty.

With hiking trails at their rear doorstep and a river nearby, Junior is never bored or left wanting. On hikes, he wears a vibration (not shock) collar when off-leash with his friends. Vibration alerts him to return to Eliot-Johnson and signals good things await – namely treats – when he’s back alongside her. This type of technology was not available to breeders/owners in the past, so certainly represents a positive when it comes to training a deaf Dal.

Against all odds, this pair epitomizes what can be accomplished with the trifecta of commitment, patience and plenty of love.

To get started in AKC agility competition, click here.

And for another heartwarming story from Ranny Green….